Search

Guideline 10.1 - Basic Life Support (BLS) Training

Summary

ANZCOR Guideline 10.1 – Basic Life Support (BLS) Training outlines a comprehensive framework for the design and delivery of BLS education across all settings. Basic Life Support training strengthens the first critical links in the chain of survival—early recognition, early call for help, early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and early defibrillation using an automated external defibrillator (AED)—by equipping individuals with the skills and confidence needed to act quickly, improving the chances of survival and recovery from cardiac arrest. It is developed in line with evidence‐based educational strategies and informed by the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) treatment recommendations, which underscore the value of blended learning approaches that combine instructor‐led sessions with pre‐course preparation.

By emphasising deliberate practice, regular refresher training, and structured assessment, the guideline aims to ensure that both health care professionals and trained lay responders achieve and maintain competence in BLS. It is intended for curriculum developers, training providers, and educators seeking to deliver high‐quality, standardised BLS education that complements the age‐specific life support recommendations outlined in ANZCOR Guidelines 11 to 13.

To whom does this guideline apply?

This guideline applies to BLS trainers and trainees in relation to Adult, Paediatric, and Newborn BLS training.

Who is the audience for this guideline?

This guideline is for BLS training curriculum developers and providers, and health care professionals who provide and receive BLS training.

Conflict of interest statement

The Australian Resuscitation Council and the New Zealand Resuscitation Council credential resuscitation training curricula. Some member organisations are providers of life support training and generate income from these activities.

Recommendations

Who should training be available to?

- ANZCOR recommends that BLS trainers encourage and direct everyone to attend BLS training [Good Practice Statement].

- ANZCOR supports the ILCOR Kids Save Lives Statement61 and recommends BLS education is provided in schools [Good Practice Statement].

- ANZCOR recommends BLS training for likely rescuers of populations at high-risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) (examples include recognised first responder organisations such as surf lifesaving, fire and rescue) [CoSTR 2020, strong recommendation, low-to-moderate–certainty evidence].

What should training include?

- BLS courses should include learner instruction and assessment on the following elements outlined in ANZCOR guidelines for Adults, Children, Infants and Newborns:

- Assessment and management of dangers.

- Assessment of responsiveness.

- Sending for help.

- Opening and clearing the airway.

- Assessment of normal breathing.

- Identifying the need for CPR once unresponsive and absence of normal breathing is established.

- Performing effective, high-quality chest compressions.

- Performing effective ventilation (mouth to mouth and mouth to mask or barrier device rescue breathing must be taught and assessed in any training program).

- Perform safe defibrillation using an AED (including how to access public defibrillation networks).

- ANZCOR suggests that all BLS courses should have a robust process for continuous evaluation and quality improvement [Good Practice Statement].

- ANZCOR suggests that resuscitation education should be tailored to the learner audience, local environment and available resources in terms of both appropriateness of learning objectives and selection of equipment and adjuncts with which to conduct BLS training [Good Practice Statement].

How should training be delivered?

- ANZCOR recommends that pre-course preparation is provided [CoSTR 2020, strong recommendation, very low to low certainty of evidence].

- ANZCOR recommends a blended learning approach, including a face-to-face component, as opposed to a non-blended approach (online or video only) for life support training where resources and accessibility permit its implementation [CoSTR 2022, strong recommendation, very low–certainty evidence].

- ANZCOR suggests that stepwise training should be the method of choice for skills training in Basic Life Support [CoSTR 2022, weak recommendation, very low-certainty evidence].

- ANZCOR suggests that spaced learning (training or retraining distributed over time) may be used instead of massed learning (training provided at one single time point) [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence].

- ANZCOR recommends instructor-led training (with manikin practice with feedback device) or the use of self-directed training with video kits (instructional video and manikin practice with feedback device) for the acquisition of CPR theory and skills in layperson adults and high school–aged (>10 years of age) children [CoSTR 2024, strong recommendation, moderate-certainty evidence].

- ANZCOR recommends instructor-led training (with AED scenario and practice) or the use of self-directed video kits (instructional video with AED scenario) for the acquisition of AED theory and skills in layperson adults and high school–aged (>10 years of age) children [CoSTR 2024, strong recommendation, low-certainty evidence].

- ANZCOR suggests that BLS video education (without manikin practice) be used when instructor-led training or self-directed training with video kits (instructional video plus manikin with feedback device) is not accessible or when quantity over quality of BLS training is needed in adults and in children [CoSTR 2022, weak recommendation, low-certainty evidence].

- ANZCOR suggests that BLS training can be provided to school-aged children by schools in different formats – using self-instructive video kits, online, and teacher led BLS skills in class [Good Practice Statement].

- ANZCOR recommends that for BLS skill and knowledge assessment, learners must be able to physically demonstrate CPR skills and knowledge on a manikin to the best of their ability. Solely computer-based systems do not fulfil this requirement [CoSTR 2020, strong recommendation, low-certainty evidence].

- ANZCOR suggests the use of feedback devices that provide directive feedback on chest compression rate, depth, release, and hand position during training [CoSTR 2024, weak recommendation, low-certainty evidence]. If feedback devices are not available, we suggest the use of tonal guidance (e.g., music or metronome) during training to improve compression rate only [CoSTR 2024, weak recommendation, low-certainty evidence].

- ANZCOR suggests the use of high-fidelity manikins when training centres/organisations have the infrastructure, trained personnel, and resources to maintain the program [CoSTR 2024, weak recommendation, very-low-certainty evidence].

- ANZCOR suggests the use of low-fidelity manikins if high-fidelity manikins are not available [CoSTR 2024, weak recommendation, low-certainty evidence].

- ANZCOR suggests that scenarios which integrate psychomotor skills, non-technical skills, clinical decision making, and reflect the environment in which candidates may be required to perform CPR are more important than the technical fidelity of the manikin [Good Practice Statement].

- ANZCOR suggests that the use of augmented reality or traditional methods be used for basic life support training of lay people and healthcare providers [CoSTR 2023, weak recommendation, very low quality of evidence].

- ANZCOR suggests that resuscitation education be configured to account for local resource availability in terms of both appropriateness of learning objectives and selection of equipment and adjuncts with which to conduct BLS training [Good Practice Statement].

How often should training take place?

- ANZCOR suggests that more frequent manikin-based refresher training for learners of BLS courses may be better to maintain competence compared with standard retraining intervals of 12 to 24 months [CoSTR 2015, weak recommendation, very-low-certainty evidence]. In making this recommendation, ANZCOR considers the rapid decay in skills after standard BLS training to be of concern for patient care. Initial training must always include specific plans for refresher training.

Who should deliver BLS training?

- ANZCOR suggests trainers/facilitators (for courses for laypersons or healthcare professionals) must have received appropriate instruction qualifications in facilitation of learning and must receive facilitation updates on a regular basis [CoSTR 2010, weak recommendation, very-low-certainty evidence].

- ANZCOR suggests that educators who use high-fidelity manikins and simulators must have adequate knowledge and familiarity with the capabilities of their training devices and their operation in a BLS scenario environment [Good Practice Statement].

How long should training be?

- ANZCOR recommends that the length of training should reflect the learning needs of the learner and their role [Good Practice Statement].

Definitions

- For the purposes of this guideline, the terms Basic Life Support (BLS), Advanced Life Support (ALS) and Health Care Professional are defined in the Australian and New Zealand Resuscitation Councils glossary.

- Blended learning: An educational approach that combines face-to-face and online approaches.1

- Deliberate practice: Activities that have been specifically designed to improve the current level of performance in which weaknesses are systematically identified and addressed to move on to the next level.2

- Fidelity: The degree to which a simulation replicates real‐life clinical scenarios. This includes both the technical or “hardware” fidelity (e.g. high‐fidelity manikins that provide realistic physiological responses) and the scenario fidelity—that is, how well the simulated environment incorporates realistic clinical cues, patient responses, and the integration of psychomotor skills, non‐technical skills, and clinical decision‐making.3

- Insitu training: Workplace-based simulation-based resuscitation training.4

- Instructor-led training: Education or training (e.g., lecture, simulation, skills demonstration, skills feedback) that occurs in the presence of a BLS instructor.5

- Mastery: The learner can consistently demonstrate a predefined level of competence for a specific skill or task.2

- Self-directed, digitally based BLS training Any form of digital (e.g., video, phone application [app] based, internet based, game based, virtual reality, augmented reality) education or training for BLS that can be completed without an instructor, except for mass media campaigns (e.g., television, social media education).5

BLS courses

This guideline assumes that the quality of resuscitation and outcomes of the victims of cardiac arrest are improved with the acquisition of BLS knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviours.6 Therefore, the design and delivery of resuscitation education plays an important role in promoting learning and retention of BLS knowledge and skills.2

Participation in Basic Life Support training courses is known to empower individuals and communities, increase bystander CPR, and improve the outcomes of victims of cardiac arrest. BLS guidelines are based on best evidence and should be combined with the educational premise that "simple is best" to teach the skills and knowledge associated with Basic Life Support. The trainers/facilitators of resuscitation techniques should base their teaching on the target audience and their educational needs and/or practice requirements. Therefore, some interpretation of the guidelines may be necessary to ensure that simple, sensible resuscitation practices are taught and learned.7-9

Regardless of the recency of CPR training or re-training, attempting resuscitation should be encouraged.

ANZCOR recommends BLS trainers encourage and direct everyone to attend BLS training [Good Practice Statement].

ANZCOR supports the ILCOR Kids Save Lives Statement61 and recommends BLS education is provided in schools [Good Practice Statement].

ANZCOR recommends BLS training for likely rescuers of populations at high-risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest [CoSTR 2023, strong recommendation, low-to-moderate–certainty evidence].

ANZCOR believes that organisations and individuals experienced in resuscitation training are best positioned to contextualise the above principles into their training programs [Good Practice Statement].

Pre-course preparation

Pre-course preparation should:

- be made available to participants

- be tailored to participants’ learning needs

- be aligned with intended learning outcomes

- optimise participant engagement and active learning.

Pre-course preparation is recommended as part of resuscitation courses.10 Pre-course learning may be facilitated by a variety of tools (e.g., computer-assisted learning tutorials, written self-instruction materials, video-based learning, textbook reading, and pre-tests). Blended learning models (e.g., independent electronic learning coupled with a reduced-duration face-to-face course time) have been reported to achieve similar learning outcomes and substantial cost savings.11

Any method of pre-course preparation that aims to reduce instructor-to-learner face-to-face time should be formally assessed to ensure equivalent or improved learning outcomes compared with traditional fully instructor-led courses.10

There are various strategies of pre-course learning. Large, published studies have investigated diverse methods of pre-course learning (e.g., manuals, online simulators) as well as how pre-course learning interconnects with the course (e.g., whether it provides additional material or replacement of material within the course). Blended learning models (e.g., independent electronic learning coupled with a reduced-duration face-to-face course time) have been reported to achieve similar learning outcomes and substantial cost savings.12

At a minimum, the pre-course preparation should include the course objectives, pre-requisite knowledge, and links for candidates to achieve such knowledge, course outline, method of delivery (online, face-to-face), and assessment criteria. This information should be provided with sufficient time for participants to assimilate the knowledge. There is insufficient evidence to make clear recommendation for a specific method or timeframe.

ANZCOR recommends that pre-course preparation is provided [CoSTR 2022, strong recommendation, very low to low certainty of evidence].

ANZCOR recommends a blended learning approach, including a face-to-face component, as opposed to non-blended approach (online or video only) for life support training where resources and accessibility permit its implementation [CoSTR 2022, strong recommendation, very low–certainty evidence].

Course content

The foundation of any BLS education should be the ANZCOR guidelines. For BASIC life support education, ANZCOR suggests that the following guidelines be consulted to inform content related to that guideline.

Figure 1: BLS elements and corresponding ANZCOR guidelines

|

BLS element |

Refer to: |

|

DANGER |

ANZCOR Guideline 2 – Managing an emergency |

|

RESPONSE |

ANZCOR Guideline 2 – Managing an emergency ANZCOR Guideline 3 - Recognition and management of the unconscious person |

|

SEND FOR HELP |

ANZCOR Guideline 2 – Managing an emergency ANZCOR Guideline 3 - Recognition and management of the unconscious person |

|

AIRWAY |

ANZCOR Guideline 4 - Airway |

|

BREATHING |

ANZCOR Guideline 5 - Breathing |

|

CPR |

ANZCOR Guideline 6 Compressions ANZCOR Guideline 8 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation |

|

DEFIBRILLATION |

ANZCOR Guideline 7 Defibrillation |

|

Paediatric BLS |

ANZCOR Guideline 12.1 Paediatric Basic Life Support for health professionals |

|

Newborn BLS |

ANZCOR Guideline 13.1- Introduction to Resuscitation of the Newborn ANZCOR Guideline 13.4 Airway management and mask ventilation of the Newborn ANZCOR Guideline 13.6 Chest compressions during resuscitation of the Newborn |

|

Teamwork, communication, and leadership |

As relevant to the learner’s role |

BLS training involves the acquisition of specific knowledge, skills (psychomotor, teamwork, communication), and attitudes with the goal of maximising resuscitation performance, and therefore improving survival outcomes.2

BLS Education Tailored to Specific Populations

In 2024, a scoping review was conducted to explore whether BLS training tailored for non-healthcare professionals, such as individuals with disabilities or special needs, could offer benefits over standard courses. Most studies focused on groups with Down syndrome, blindness, or hearing impairments, but no studies directly compared tailored courses with standard ones. Results were mixed, with some tailored approaches showing limited improvements (e.g., only a small percentage of participants with Down syndrome achieved high-quality chest compressions) and others facing challenges (e.g., difficulties with emergency activation for those with hearing impairments). The task force concluded that while tailored BLS training appears feasible and could expand the pool of potential bystander CPR providers, further research and a structured, validated approach are needed to confirm its effectiveness.13

ANZCOR suggests that BLS training should be designed with the target patient population in mind. BLS courses should have core components that may be supplemented by context-specific components [Good Practice Statement].

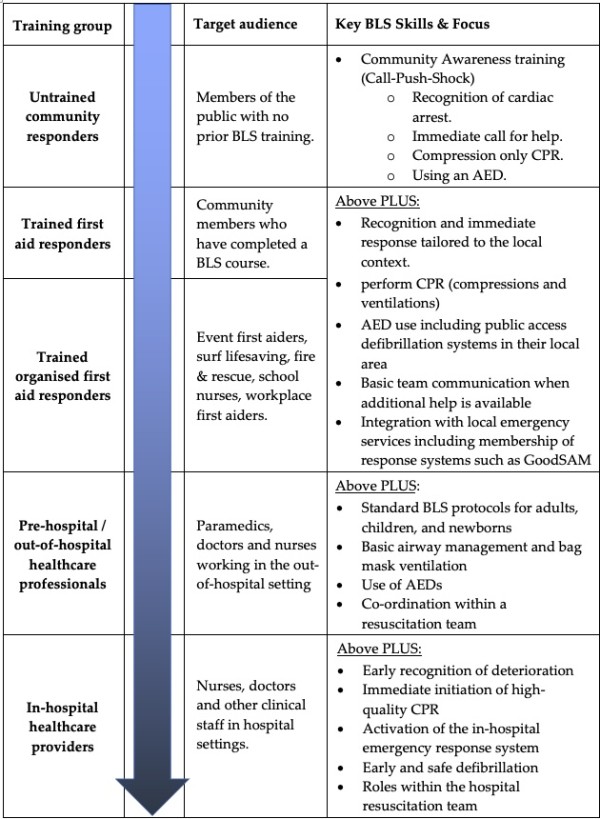

Community Awareness versus Formal BLS Training

In this guideline, a deliberate distinction is made between community awareness education and formal BLS training. Community awareness initiatives, such as those delivered via public campaigns, school-based programs, and non-accredited or online first aid awareness activities, aim primarily to increase the number of people willing and able to act in the event of a cardiac arrest. In this context, simple, action-focused messaging such as "Call-Push-Shock"—emphasising early recognition, immediate emergency activation, performing chest compressions, and defibrillation—is appropriate. These programs are intended to be accessible, rapidly scalable, and to prioritise immediate life-saving actions without the complexity of formal BLS training.

In contrast, formal BLS training refers to structured programs aligned with ANZCOR guidelines, delivered either through accredited first aid courses or organised healthcare or workplace-based education. Formal BLS training includes instruction and assessment on the full DRSABCD sequence, high-quality chest compressions, effective ventilation (mouth-to-mouth or using barrier devices), and safe defibrillation with an Automated External Defibrillator (AED). This level of training prepares learners to provide comprehensive basic life support in a variety of settings.

It is the intent of the ANZCOR that organisations choose the appropriate teaching approach based on the educational setting and target audience. For broad community education programs where speed, simplicity, and widespread reach are priorities, "Call-Push-Shock" messaging with compression-only CPR is recommended. For formal BLS or First Aid training courses, especially those aiming for certification or competence assessment, full DRSABCD training incorporating compressions and ventilations should be delivered.

Figure 2: Aligning BLS Messaging and Training Approaches with Target Audience

Teamwork

Teamwork, communication, and leadership are increasingly recognised as important factors contributing to patient safety and outcomes in healthcare.14 In the context of BLS, teamwork, communication, and leadership will differ according to the context of the learner and their role when providing BLS in practice. For example, some first responders may need to instruct others to assist in BLS in an OHCA situation, whereas others will form part of a team approach to BLS (e.g., ward-based health professionals in a hospital). Therefore, BLS training should include specific education on teamwork, communication, and leadership in a BLS situation that is relevant to the context of the learner.2,4,15

ANZCOR recommends that BLS courses should include instruction and assessment on the following elements outlined in ANZCOR guidelines for Adults, Children, Infants and Newborns [Good Practice Statement]:

- Assessment and management of dangers.

- Assessment of responsiveness.

- Sending for help.

- Opening and clearing the airway.

- Assessment of normal breathing.

- Identifying the need for CPR once unresponsive and absence of normal breathing is established)

- Performing effective, high-quality chest compressions

- Performing effective ventilation (mouth to mouth and mouth to mask or barrier device rescue breathing must be taught and assessed in any training program).

- Perform safe defibrillation using an AED (including how to access public defibrillation networks).

ANZCOR suggests that resuscitation education should be tailored to the learner audience and the local environment and available resources in terms of both appropriateness of learning objectives and selection of equipment and adjuncts with which to conduct BLS training [CoSTR 2023, weak recommendation, very-low-certainty evidence].

ANZCOR suggests that all BLS courses should have a robust process for continuous evaluation and quality improvement [Good Practice Statement].

Course delivery / educational approaches

There is a wide range of course delivery options available for resuscitation training, from instructor-led training to self-directed training to a blended approach involving both modes. The acquisition of different BLS skills may vary across different mediums and age groups. Also, there are known barriers that exist for instructor led BLS training (e.g., time, cost, and accessibility) coupled with the need to make BLS training available to as many people as possible.5 Ultimately, BLS education needs to optimise the likelihood that a learner will be able to master key resuscitation skills. BLS educators should plan to deliver education experiences that allow for deliberate practice, where learners practice key skills (multiple times if necessary), receive direct feedback on performance and give opportunity for learners to improve until they gain mastery. 2,5

In considering BLS training delivery, evidence demonstrates that any form of BLS education enhances bystander knowledge, confidence, and willingness to perform CPR compared with no training. Dispatcher-assisted CPR (DA-CPR) significantly improves survival compared to no bystander intervention; however, survival rates are higher when CPR is initiated by a trained bystander compared to DA-CPR. These findings underscore the critical role of DA-CPR as an immediate support mechanism for untrained bystanders, while also highlighting that expansion of structured BLS training remains essential to maximise survival outcomes following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.5

Establishing a Safe Learning Environment

Establishing a psychologically safe training environment includes: clarifying expectations; engaging in an explicit and collaborative agreement in which both instructors and learners commit to what can reasonably occur to make the situation as real as possible whilst acknowledging the limitations of a simulation environment; and enacting a commitment to respecting learners and their psychological safety. The instructor-learner relationship should be collaborative and there should be consistency between what instructors say and do as well as consistency between instructors.16 Instructors should be aware of the intended learning outcomes so that training can be tailored to specific learners or learner groups.2 Intended learning outcomes should be learner-focused and not solely meet the requirements of content delivery.2 Instructors should have a sound and clear understanding of the key instructional design features that enhance learning in a BLS course and should have specific training in feedback and debriefing.2

Knowledge

Methods used to teach the knowledge component of BLS training should align with and achieve the intended learning outcomes. It is acknowledged that participants will have varying levels of prior knowledge, and this needs to be considered in decisions regarding the most appropriate teaching method. For example, new learners may require more detailed initial explanations. Options for delivery of knowledge should be flexible and may include self-directed learning, use of written or online materials, lectures or small group sessions.

Skills

Mastery “implies that a learner can consistently demonstrate a predefined level of competence for a specific skill or task”.2p e4 Therefore, resuscitation education experiences should enable learners to practice fundamental resuscitation skills, receive directed feedback, and improve their performance until mastery is achieved.2

Participants should demonstrate satisfactory performance in:

- individual skill and scenario-based components of BLS

- capacity to operate within a team.

Participants should demonstrate an understanding of the:

- indications for resuscitation

- indications for equipment and potential complications of procedures

- sequencing and prioritisation of resuscitation interventions.

The 2023 ILCOR CoSTR suggests that stepwise training, an instructional approach for resuscitation skill training that utilises several steps, should be the method of choice for skills training in resuscitation [CoSTR 2023, weak recommendation, very-low certainty of evidence].17 The optimal stepwise training approach (including the number and types of steps) is likely to be dependent on the type of skills taught and therefore should be adapted appropriately to that skill.18

Consider learning styles

Educators should be cognisant that different people will have preferred sensory inputs when they are learning or communicating, and these preferences may change over time. These sensory inputs include what they can see, what they can read and what they can touch and feel. When teaching BLS knowledge and skills, educators should try to include elements of all sensory learning styles to cater to all learners.19

Model / exemplar demonstration

Whenever possible, educators should provide a model or exemplar performance for learners. This may be a practical demonstration by the educator/education team or a standardised exemplar video.2

Blended learning approach

A blended learning approach utilises some online content that supports face-to-face learning. A blended learning approach is grounded in a strong framework from educational theory, and the blended learning approach has resulted in similar or better educational outcomes for learners. Blended learning also enables consistent messaging regarding content, which can be particularly useful for pre-course preparation.1 A non-blended learning approach (i.e., face-to-face only or online only) is an acceptable alternative where resources or accessibility do not permit the implementation of a blended learning approach.1

ANZCOR recommends the option of blended learning (i.e., online and face-to-face) where resources and accessibility permit its implementation [CoSTR 2022, strong recommendation, very low-to-low certainty evidence].

Instructor led vs. digital training

Evidence shows that adequate training outcomes for some BLS skills (included use of an AED) may not be achieved with video-only/digital training; therefore instructor-led training (including deliberate practice with a manikin, potentially a manikin with feedback capability and including a scenario that gives the opportunity to practice with an AED) or a blended approach remain the preferred options.5

Digital training has proven useful for pre-course preparation and for the reinforcement of theoretical knowledge and processes related to BLS.1 It enables wider access to education during periods of high need (e.g., pandemics); provides ongoing access to learning materials at no additional cost; is particularly valuable for remote and lower resource settings, and can reduce the duration of face-to-face training.1,5 However, while digital methods are effective for refreshing knowledge and understanding, the maintenance and refinement of practical BLS skills still require hands-on practice with appropriate feedback. Therefore, digital training should be considered as part of a blended approach to BLS education, supporting but not replacing the need for physical skill practice.5

Whichever method is utilised, instructors should ensure that digital and instructor led materials are regularly revised and updated to ensure that training complies with current BLS recommendations.5

ANZCOR recommends instructor-led training (with manikin practice with feedback device) or the use of self-directed training with video kits (instructional video and manikin practice with feedback device) for the acquisition of CPR theory and skills in layperson adults and high school–aged (>10 years of age) children [CoSTR 2024, strong recommendation, moderate-certainty evidence].

ANZCOR suggest that BLS video education (without manikin practice) be used when instructor-led training or self-directed training with video kits (instructional video plus manikin with feedback device) is not accessible or when quantity over quality of BLS training is needed in adults and in children [CoSTR 2022, weak recommendation, low-certainty evidence].

ANZCOR suggests that BLS training can be provided to school aged children by schools in different formats, using self-instructive video kits, online, and teacher led BLS skills in class [Good Practice Statement].

Spaced or distributed practice:

Spaced learning (training or retraining distributed over time) may be used instead of massed learning (training provided at one single time point) to improve skill retention and reduce training costs. Evidence shows that after resuscitation courses, skills and knowledge deteriorate after 1-6 months without ongoing practice.2 There is growing evidence to suggest that spaced learning can improve skill retention (performance 1 year after course conclusion), skill performance (performance between course completion and 1 year), and knowledge at course completion.5 Increasing the frequency of training may improve training outcomes and mitigate skill deterioration.2

ANZCOR suggests BLS training can be delivered by either a spaced learning approach or a massed learning approach [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence].

Use of cognitive aids:

Managing cardiac arrest and other emergencies is inherently complex. Cognitive aids—such as algorithms, flow charts, checklists, posters, and digital apps—are used globally to support guideline adherence and reduce errors by offering a structured clinical framework. However, their effect on performance and patient outcomes remains uncertain. ILCOR reviewed the evidence in 2020 and did not recommend cognitive aids for laypersons during training and real CPR; however, they were suggested for the training of health care professionals. Since then, new evidence has been published, triggering an update of the systematic review in 2024.13,20,21

A review of 29 simulation studies on cognitive aids in resuscitation found that, despite very low certainty of evidence and significant study heterogeneity, many tools ranging from augmented reality decision support and interactive apps to noninteractive checklists can improve protocol adherence and task performance across neonatal, paediatric, adult ALS, and other emergency scenarios. However, improvements in CPR quality were inconsistent, and a few studies reported undesirable effects such as delays in initiating compressions or calling for help. Notably, none of the studies examined cognitive aids as educational tools, and no meta-analysis was possible due to the diversity of methods and outcomes.13

The 2020 treatment recommendation was based on trauma resuscitation studies, which report teams using aids report better adherence to guidelines, fewer errors, and perform key tasks more frequently.3 The 2024 systematic review did not examine the use of cognitive aids in health professional or lay rescuer training in resuscitation so no recommendation for or against was issued.13

ANZCOR believes it is reasonable to use cognitive aids (e.g., checklists, flow charts) during resuscitation training, provided they do not delay the start of resuscitative efforts. It is preferable that these cognitive aids should be the same or similar, where practical, to those available to participants in clinical practice. BLS trainers should be aware that cognitive aids may result in adverse events, such as the promotion of fixation errors and groupthink,22 impair communication among team members,23 and be distracting if not well-developed.3

ANZCOR suggests that the use of cognitive aids may be considered for use in BLS training [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence]. It is preferable that these cognitive aids should be the same or similar, where practical, to those available to participants in clinical practice [Good Practice Statement].

CPR prompt or feedback devices

CPR prompt or feedback devices may be considered during CPR training for health care professionals. The use of CPR feedback or prompt devices during CPR in clinical practice or CPR training is intended to improve CPR quality as a means to improve ROSC and survival.10,24 The forms of CPR feedback or prompt devices include audio and visual components such as voice prompts, metronomes, visual dials, numerical displays, wave-forms, verbal prompts, and visual alarms. Visual displays enable rescuers to see compression-to-compression quality parameters, including compression depth and rate.24 Audio prompts may guide CPR rate (e.g., metronome) and may offer verbal prompts to rescuers (e.g., “push harder,” “good compressions”).24

The 2015 and 2020 ILCOR CoSTRs3,6 did not identify any studies related to the use of real-time audiovisual feedback and prompt devices during CPR training and the critical outcomes of improvement of patient outcomes and skill performance in actual resuscitations. The 2020 review identified 14 simulation-based studies (13 randomised control trials (RCTs)). A review of 5 studies (four studies of 1029 participants in adult CPR training25-28 and one study of 36 participants in neonatal CPR training)29 showed substantial skill decay 6 weeks to 12 months after training with and without the use of a feedback device. For the important outcome of skill performance at course conclusion, a review of 28 studies25-52 showed limited improvements in CPR quality (i.e., compression depth, compression rate, chest recoil, hand placement, hands-off time, and ventilation) with a feedback device. An evidence update in 2024 found that feedback devices improve CPR quality, including long-term retention. Augmented reality-assisted feedback enhances all CPR metrics. Real-time feedback devices in simulated infant CPR showed similar performance to non-feedback CPR. In observational studies, defibrillators with CPR feedback features led to better adherence to AHA guidelines for chest compression rate and fraction.13 3,6,10,13,24-52

ANZCOR suggests the use of feedback devices that provide directive feedback on compression rate, depth, release, and hand position during training [CoSTR 2024, weak recommendation, low-certainty evidence]. If feedback devices are not available, we suggest the use of tonal guidance (examples include music or metronome) during training to improve compression rate only [CoSTR 2024, weak recommendation, low-certainty evidence].

Gamified Learning as an educational approach:

Younger generations’ comfort with technology suggests that active, peer-engaging teaching strategies may be effective adjuncts to instruction. Gamification using game elements like competition, points, levels, and leaderboards has shown mixed results in enhancing CPR knowledge and skills, whether used alone or as pretraining. A 2024 systematic review of 13 studies (6 RCTs and 7 observational) on gamified resuscitation training, mostly involving healthcare professionals and a few high school students, found mixed but generally positive effects. Digital platforms (online interfaces, leaderboards, and smartphone apps) were most used, with a couple of studies using board and card games. Some RCTs and observational studies showed improved CPR performance (e.g., chest compression quality and faster intervention times), enhanced knowledge in neonatal resuscitation, and increased self-reported confidence in ALS scenarios. However, due to high study heterogeneity and low certainty of evidence, no meta-analysis was performed, and none reported on process outcomes, costs, or critical clinical outcomes.13

ANZCOR suggests the use of gamified learning be considered as a component of resuscitation training for all types of BLS and ALS courses [CoSTR 2023, weak recommendation, very low–certainty evidence].

Using a stepwise approach for training

The most appropriate training method for resuscitation skills has been long debated, particularly on a stepwise approach and the number of steps to be used. It is known from practice that many instructors do not adhere to a particular stepwise approach in their teaching. The optimal stepwise training approach (including the number and type of steps) may be dependent on the learner and the type of skills taught. A variation of the number and kinds of steps should be tailored to the learner and adapted to the nature of the skill taught.3,4 This may include the opportunity for learners to be given more time or for a different educational approach to be used if the standard approach is not working for them to attain the knowledge and skills needed.2

ANZCOR suggests that stepwise training should be the method of choice for skills training in Basic Life Support [CoSTR 2022, weak recommendation, very low-certainty evidence].

Rapid cycle deliberate practice as an educational approach

Rapid cycle deliberate practice (RCDP) is a training method that uses stop-and-go practice with immediate feedback, allowing ample repetition in a safe, non-judgmental environment to improve clinical outcomes. It is distinct from simple repetitive practice, and in 2024, a systematic review was initiated since ILCOR had not previously evaluated its evidence in resuscitation training.13

Across seven RCTs and one observational study of RCDP in simulated resuscitation training (involving medical students, interns, residents, physicians, and mixed clinical staff across adult, paediatric, and neonatal scenarios), no clinical outcomes were reported. Meta-analysis of time to chest compressions in paediatric/neonatal settings showed very low-certainty evidence of no benefit compared with after-event debriefing, although one observational study noted a shorter time to compression initiation. Other findings were mixed; one RCT showed improved time to positive-pressure ventilation, some studies reported shorter defibrillation times and pauses, and improvements in compression fraction were noted. However, skill retention at four months was similar between groups, protocol adherence results were inconsistent, and while team leader performance improved in one study, participants rated RCDP as less effective for teaching.13

ANZCOR suggests it may be reasonable to include RCDP as an instructional design feature of BLS and ALS training [CoSTR 2023, weak recommendation, very low–certainty evidence].

Course duration

Little evidence exists to determine BLS training duration. In considering course duration, an element of flexibility should be incorporated to allow for learners who need more time to practice skills and gain the required knowledge.2

ANZCOR suggests that the duration of the training should reflect the learning needs of the learner and the requirements of their role [Good Practice Statement].

Performance Feedback and Assessment

Minimum Passing Standard

The minimum passing standard should be made clear to learners from the very beginning. Educators should develop key metrics and clear assessment tools. This allows learners and educators to establish performance goals for both mastery learning and deliberate practice.2 Standard performance should be an observable behaviour and set based on improving patient outcomes and process measures (time, accuracy, best practice, local protocols, or a checklist of standard performance).2

Performance Feedback

Feedback is defined as information regarding performance compared with a specific standard; whereas, debriefing is defined as a reflective analysis or prior performance between 2 or more individuals with the aim of improving future performance.3 Performance feedback is vital to maintaining and improving clinical skills, even for experienced clinicians.2,53 Effective feedback should be specific, timely, actionable, and be learner specific. Feedback should also enable the learner to identify positive aspects of performance and those requiring improvement.2,16 Instructors should be cognisant that learners have difficulty using feedback that threatens their self-esteem or conflicts with their perceptions of self.54,55 Careful consideration must be given to feedback, as the effect of feedback can be positive or negative on learning.54,55

A systematic review and meta-analyses of the effectiveness of feedback during procedural skills training using simulation-based medical education showed that feedback was associated with significantly improved skill outcomes.56 There was no significant difference between formative and summative feedback for skill outcomes assessed immediately at the end of the intervention or when skills were assessed at least 5 days post-training.56 When compared to a single source of feedback, multiple sources (e.g., instructor and visual) of feedback enhanced learning outcomes.56

ANZCOR suggests data-driven, performance-focused feedback and debriefing of rescuers during training [Good Practice Statement].

Assessment

Assessment is defined as “any systematic method of obtaining information from tests and other sources, used to draw inferences about characteristics of people, objects or programmes”.57

In the context of BLS courses, the domains that should be assessed include resuscitation knowledge, technical skills (e.g., chest compressions), and nontechnical skills (e.g., leadership or communication). These domains are complex, so the construct being assessed must be clearly identified.2 Assessment methods may include written assessments (e.g., multiple-choice questions) and assessments of performance (e.g., a simulated resuscitation scenario or demonstration of a specific technical skill).2 Assessments should measure elements of resuscitation that are important for patient outcomes rather than what is easy to assess,2 and should be performed for both the individual (e.g., delivery of guideline compliant chest compressions) and team performance if applicable.2

Assessment data may be derived from direct observation, retrospective video review, or CPR feedback devices.2 Assessment for learning (formative assessment) should occur throughout the course to inform instructor feedback and coaching. Assessment of learning (summative assessment) typically occurs at the end of a BLS course as a measure of the effectiveness of the educational intervention and for certification.2 Assessment tools should be valid, reliable, and reflect the course learning outcomes. Assessment methods should be reproducible.2

Assessment of BLS knowledge and skills may include written and practical testing components. The use of written assessment alone is insufficient. 4,20,21 A 2020 ILCOR systematic review of end-of-course testing versus continuous assessment found no studies that addressed the PICOST question, and no treatment recommendation was made.3

ANZCOR suggests that assessment of BLS skills during and/or after training should be considered as a strategy to improve learning outcomes [Good Practice Statement].

ANZCOR recommends that at the completion of the course, learners must be able to physically demonstrate CPR skills and knowledge on a manikin, to the best of their physical ability. Solely computer-based systems do not fulfil this requirement [CoSTR 2010, weak recommendation, very low–certainty evidence].

BLS assessments that are impacted by physical limitations of the candidate

Several studies have examined the effect of the anthropometric factors on the quality of CPR. It has been found that the height, weight, and muscle strength of candidates will impact the ability of that candidate to achieve guideline compliant compressions with both compression depth and recoil affected.58-60 Some of these factors may develop over time due to acute or chronic conditions. By extension, candidates may also have difficulty achieving the minimum passing standard of a BLS assessment due to anthropometric factors. Given that any attempt at CPR is better than no attempt, and in recognition of factors that cannot be altered, flexibility in the minimum passing standard may be needed in these situations. It is suggested that candidates still demonstrate what they can achieve within their limitations. This is consistent with the fact that if they are the first on scene they should attempt CPR to the best of their abilities and that each candidate and assessor should have an awareness of what those limitations are. Candidates should verbalise what they would do if they were first to discover victim (start compressions), how they would alert others in a resuscitation situation of their physical limitations, and how this might be managed (e.g., undertake a different role, or change person on compressions more frequently).

Equipment / resources

The resources needed to teach BLS do not need to be complex, and many successful BLS training programs use simplified training devices with excellent outcomes.61

Manikin Fidelity

High fidelity manikins are computerised, full-body manikins that can be programmed to provide realistic physiological response to learner’s actions. There is insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of techniques such as high-fidelity manikins and workplace-based simulation-based resuscitation training compared with training on low-fidelity manikins and education centre-based training.10

High-fidelity training compared with low-fidelity training has been shown to have a moderate effect on improved skills performance at course completion (very-low-certainty evidence from 12 RCTs with 726 participants),62-73 but no benefit on skills performance at 1 year62 63 High-fidelity training compared with low-fidelity training had no benefit in knowledge at course conclusion (low-certainty evidence from 8 RCTs with 773 participants63-66,71,72,74,75 and 1 non-RCT with 34 participants).76

Perhaps more important is designing resuscitation training that is contextual to each learner’s real-world scope of practice incorporating learner and environmental factors.2 Learner factors include age, background, clinical experience, cognitive load, expectations, emotions, and stress levels. Environmental factors include training setting, devices and media used, manikin/simulator features, local institutional and societal considerations.2

ANZCOR suggests that training organisations used the resources available to them and that the use of low-fidelity manikins is acceptable for BLS training [Good Practice Statement].

ANZCOR suggests the use of high-fidelity manikins when training centres/organisations have the infrastructure, trained personnel, and resources to maintain the program [CoSTR 2024, weak recommendation, very-low-certainty evidence].

ANZCOR suggests that the fidelity of the scenario is more important than the fidelity of the manikin [Good Practice Statement].

Immersive Technologies as an educational approach

Current training methods for both laypeople and health care professionals are often inadequate, leading to poor skill acquisition and rapid decay. Alternative strategies, such as immersive technologies, virtual reality (VR), and augmented reality (AR), offer interactive, real-time simulation experiences that may enhance learning and improve cardiac arrest outcomes. These technologies can complement traditional methods like video, manikin-based, and online training, however, they are often costly. Despite their use in various educational settings, the overall impact of VR and AR on learning and performance remains unclear, which prompted a systematic review in 2024.

Due to high heterogeneity across studies in terms of design, intervention type, and outcome measures, no meta-analysis was possible. Out of 18 studies, 3 focused on AR for BLS training, two with mixed results on CPR depth. VR was explored in 12 studies: 9 for BLS and 3 for ALS. VR showed mixed results compared to traditional methods, with some studies favouring VR for knowledge acquisition and others noting no difference in CPR performance. Notably, those in instructor-led BLS training typically performed better in CPR depth, rate, and other skills than those trained with VR. Additionally, some studies found no lasting improvements in knowledge retention or CPR performance after VR training, though one study showed greater willingness to perform CPR with instructor-led training.13

ANZCOR suggests the use of either AR or traditional methods for BLS training of laypeople and health care professionals [CoSTR 2023, weak recommendation, very low–certainty evidence].

ANZCOR suggests against the use of VR only for BLS and ALS training of laypeople and health care professionals [CoSTR 2023, weak recommendation, very low–certainty evidence]. If used, VR should be combined with instructor led training.

Basic Life Support re-training and refresher training

The evidence related to optimal retraining intervals for resuscitation education is limited in both quantity and quality. The optimal interval for retraining meaning re-completion of a full BLS course has not been established. However, repeated refresher training is needed for individuals who are not performing resuscitation on a regular basis.2

What is well established is that the frequency of BLS re-training or refresher activities will be influenced by how quickly skills and knowledge gained in training decay over time. CPR skills are known to deteriorate within weeks to months after traditional single-encounter courses and well before traditional retraining intervals of 1 to 2 years.2,77

Health professionals’ exposure to cardiac arrest remains relatively low. Victorian data shows that paramedics are exposed to an average 1.4 (IQR=0.0-3.0) out-of-hospital cardiac arrests per year, with an average interval of 163 days between exposures.78 Annually, there are approximately 10.2 million hospital admissions in Australia79 and 1.1 million in New Zealand.80 A systematic review of the frequency, characteristics, and outcomes of adult in-hospital cardiac arrests in Australia and New Zealand showed that the frequency of in-hospital cardiac arrests ranged from 1.31-6.11 per 1000 admissions in four population studies and 0.58-4.59 per 1000 in 16 cohort studies.81

Retraining cycles of 12 to 24 months are likely insufficient to maintain high-quality BLS performance.11 While the optimal formal retraining intervals remain uncertain, more frequent refresher training (brief, focused practice sessions aimed at reinforcing key skills) has been shown to benefit healthcare providers in maintaining BLS proficiency.2

Refresher training, in the form of low-dose, high-frequency sessions using manikins, may be a practical, cost-effective solution. Sessions should be brief, typically 5 to 15 minutes in duration and scheduled frequently, for example, on a weekly, monthly, or quarterly basis, depending on learner needs and operational feasibility. Note: Throughout this guideline, the term "brief refresher training" refers to short, low-dose practice sessions (5 to 15 minutes in duration), aligned with the principles of low-dose, high-frequency training to support ongoing BLS skill retention. Such sessions can be integrated into daily workflow, reducing the need for full course attendance and allowing for ongoing reinforcement.82 Learning from “frequent, low-dose” compared with “comprehensive, all-at-once” instruction is effective and preferred by learners.83 Instructional methods such as RCDP,4,84 which involves repeated short simulations with immediate feedback, warrants further consideration. The role of experiential clinical exposure and feedback in retraining requires further study.

Where possible, more frequent refresher sessions (e.g., monthly) are preferred, but any increase in refresher frequency compared to traditional annual or biennial retraining is likely to improve skill retention and patient outcomes.

In line with the principles outlined for initial BLS education, refresher and retraining programs should incorporate a Minimum Passing Standard where practical. The minimum standard should be made clear to learners at the outset. Educators should define key metrics and assessment tools appropriate to the refresher context, focused on observable performance behaviours. These should aim to reinforce actions that improve patient outcomes and key process measures such as time, accuracy, adherence to best practice, or local protocols.

Figure 3: Examples of Refresher Training options for BLS Skill Retention

|

Training Method |

Session Length |

Suggested Frequency |

Focus Area |

Notes |

|

Skills station in clinical area (e.g., manikin at nurse station, paramedic depot) |

5 to 10 minutes |

Weekly or fortnightly |

Chest compressions, AED use, basic airway techniques |

Self-directed or peer-supervised; can be integrated into shift handover or breaks |

|

Short instructor-led scenario practice (e.g., ward or station simulation) |

10 to 15 minutes |

Monthly |

Full DRSABCD sequence, teamwork, communication |

May include feedback |

|

Online video review with knowledge check (without manikin) |

5 to 10 minutes |

Monthly or quarterly |

Recognition of cardiac arrest, emergency activation steps |

Supplements physical skills practice, reinforces cognitive elements |

|

Peer-paired practice sessions |

5 to 15 minutes |

Monthly |

Compressions and rescue breaths |

Encourages team familiarity and peer feedback |

|

Low-dose in situ simulation drill |

10 to 15 minutes |

Quarterly |

Full BLS response in the real environment |

Focus on systems, role allocation, and early defibrillation |

These examples are flexible and should be adapted to the learner population, available resources, and organisational needs. While more frequent practice is preferred, any increase in refresher opportunities compared to traditional annual or biennial retraining is considered beneficial for maintaining BLS knowledge and skills.

ANZCOR suggests that more frequent manikin-based refresher training for students of BLS courses may be better to maintain competence compared with standard retraining intervals of 12-24 months [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very-low-certainty evidence].

ANZCOR considers the rapid decay in skills after standard BLS training to be of concern for patient care. Initial training must always include specific plans for refresher training.

Governance and administration

Governance structures

Governance structures and processes are the essential systems and procedures of oversight for consistent delivery, maintenance of standards and review of outcomes. They should guide all courses making statements to the rules, procedures, and other informational guidelines. In addition, governance frameworks define, guide, and provide for the enforcement of these processes.

Models for the governance will vary but should incorporate aspects of:

- Defined rules and regulations

- Organisational and individual accountability

- Administration requirements before/during, and following the course

- Review processes

- Information storage

- Health and safety requirements

- Fiscal probity

- Equity

- Participant requirements

- Instructor proficiency and conduct

- Candidate selection /eligibility

- Assessment systems

- Appeal process

- Certification

The governance must comply with statutory legislative requirements and be available to all participants for review. Ongoing review of the material, structures, and participant feedback of the course should occur to ensure the substance of the course is current in the clinical and governance scope.

ANZCOR suggests that all BLS courses should have a robust process for continuous evaluation and quality improvement [Good Practice Statement].

Faculty Development

Faculty development for resuscitation course instructors remains an important element contributing to improved teaching and the learners’ outcomes in accredited life support courses. Faculty development should have an intentional focus on optimising the delivery of resuscitation curriculum in a contextualised manner for different learner groups.2 However, no clear picture of the most appropriate and most effective faculty development programs has been identified from the studies reviewed. It is recommended that any organisation offering resuscitation education should also provide faculty development programs for the teaching staff of their resuscitation programs. Different approaches need to consider the local training environment and resource availability, as well as instructors’ needs, to maximize learning outcomes of such programs. The best ways to maintain and assess instructor competency whilst concurrently maximising cost-effectiveness needs to be established by organisations individually.1,2

Instructor training should include content on, practice with, and evaluation of key instructor competencies, including:

- Knowledge and skills associated with the science of resuscitation and the science of education.

- Use of feedback devices and approaches to dealing with the most common challenges.

- Ability to effectively debrief others and facilitate peer coaching.

- Contextualisation of content to various audiences and practice settings.

- Facilitation of the development of teamwork training skills.

- Giving and receiving feedback (e.g., peer coaching).

- Reflective practice.

- Helping instructors recognise themselves as change agents.2

ANZCOR recommends that trainers/facilitators (for courses for laypersons or healthcare professionals) must have received appropriate instruction qualifications in facilitation of learning and must receive facilitation updates on a regular basis [Good Practice Statement].

ANZCOR suggests that educators who use high-fidelity manikins and simulators must have adequate knowledge and familiarity with the capabilities of their training devices [Good Practice statement].

Abbreviations

|

Abbreviation |

Meaning/Phrase |

|

AED |

Automated external defibrillator |

|

ALS |

Advanced Life Support |

|

ANZCOR |

Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation |

|

AR |

Augmented reality |

|

BLS |

Basic life support |

|

CPR |

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

|

CoSTR |

Consensus on Science with Treatment Recommendations |

|

CPR |

cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

|

ILCOR |

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation |

|

OHCA |

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest |

|

RCT |

Randomised control trials |

|

RCDR |

Rapid cycle deliberate practice |

|

VR |

Virtual reality |

References

- Wyckoff MH, Greif R, Morley PT, et al. 2022 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations: Summary From the Basic Life Support; Advanced Life Support; Pediatric Life Support; Neonatal Life Support; Education, Implementation, and Teams; and First Aid Task Forces. Circulation 2022.

- Cheng A, Nadkarni VM, Mancini MB, et al. Resuscitation Education Science: Educational Strategies to Improve Outcomes From Cardiac Arrest: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 138(6): e82-e122.

- Greif R, Bhanji F, Bigham BL, et al. Education, Implementation, and Teams: 2020 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation 2020; 156: A188-A239.

- Berg K, Bray J, NG K, et al. 2023 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations: Summary From the Basic Life Support; Advanced Life Support; Pediatric Life Support; Neonatal Life Support; Education, Implementation, and Teams; and First Aid Task Forces Circulation 2023; 148e: e187-e280.

- Wyckoff MH, Singletary EM, Soar J, et al. 2021 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations: Summary From the Basic Life Support; Advanced Life Support; Neonatal Life Support; Education, Implementation, and Teams; First Aid Task Forces; and the COVID-19 Working Group. Resuscitation 2021; 169: 229-311.

- Greif R, Lockey AS, Conaghan P, Lippert A, De Vries W, Monsieurs KG. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 10. Education and implementation of resuscitation. Resuscitation 2015; 95: 288-301.

- Larsen MP, Eisenberg MS, Cummins RO, Hallstrom AP. Predicting survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A graphic model. Annals of Emergency Medicine 1993; 22(11): 1652-8.

- Oliveira NC, Oliveira H, Silva TLC, Boné M, Bonito J. The role of bystander CPR in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: what the evidence tells us. Hellenic Journal of Cardiology 2025; 82: 86-98.

- Doan TN, Schultz BV, Rashford S, Bosley E. Surviving out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: The important role of bystander interventions. Australasian Emergency Care 2020; 23(1): 47-54.

- Soar J, Mancini ME, Bhanji F, et al. Part 12: Education, implementation, and teams: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation 2010; 81(1): e288-e330.

- Finn JC, Bhanji F, Lockey A, et al. Part 8: Education, implementation, and teams 2015 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation 2015; 95: e203-e24.

- Mancini ME, Soar J, Bhanji F, et al. Part 12: Education, implementation, and teams: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation 2010; 122(16 Suppl 2): S539-81.

- Greif R, Bray JE, Djärv T, et al. 2024 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations: Summary From the Basic Life Support; Advanced Life Support; Pediatric Life Support; Neonatal Life Support; Education, Implementation, and Teams; and First Aid Task Forces. Resuscitation 2024.

- Rosen M, DiazGranados D, Dietz A, et al. Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. American Psychologist 2018; 73(4): 433-50.

- Cooper S, Wakelam A. Leadership of resuscitation teams: ‘Lighthouse Leadership’. Resuscitation 1999; 42(1): 27-45.

- Rudolph JW, Raemer DB, Simon R. Establishing a safe container for learning in simulation: the role of the presimulation briefing. Simulation in Healthcare 2014; 9(6): 339-49.

- Berg KM, Bray J, Ng KC, et al. 2023 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recomemendations. 2023. https://ilcor.org/publications.

- AIHW. Injury in Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023.

- Bywater E, Davis J. Leading and Learning: Ambulance Victoria; 2019.

- Wyckoff MH, Greif R, Morley PT, et al. 2022 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations: Summary From the Basic Life Support; Advanced Life Support; Pediatric Life Support; Neonatal Life Support; Education, Implementation, and Teams; and First Aid Task Forces. Resuscitation 2022; 181: 208-88.

- Wyckoff MH, Greif R, Morley PT, et al. 2022 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations: Summary From the Basic Life Support; Advanced Life Support; Pediatric Life Support; Neonatal Life Support; Education, Implementation, and Teams; and First Aid Task Forces. Circulation 2022; 146(25): e483-e557.

- Kaba A, Wishart I, Fraser K, Coderre S, McLaughlin K. Are we at risk of groupthink in our approach to teamwork interventions in health care? Medical Education 2016; 50(4): 400-8.

- Marshall S. The Use of Cognitive Aids During Emergencies in Anesthesia: A Review of the Literature. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2013; 117(5).

- Perkins GD, Travers AH, Berg RA, et al. Part 3: Adult basic life support and automated external defibrillation. 2015 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation 2015; 95: e43-e69.

- Oermann MH, Kardong-Edgren SE, Odom-Maryon T. Effects of monthly practice on nursing students’ CPR psychomotor skill performance. Resuscitation 2011; 82(4): 447-53.

- Spooner BB, Fallaha JF, Kocierz L, Smith CM, Smith SC, Perkins GD. An evaluation of objective feedback in basic life support (BLS) training. Resuscitation 2007; 73(3): 417-24.

- Mpotos N, Lemoyne S, Calle PA, Deschepper E, Valcke M, Monsieurs KG. Combining video instruction followed by voice feedback in a self-learning station for acquisition of Basic Life Support skills: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Resuscitation 2011; 82(7): 896-901.

- Zapletal B, Greif R, Stumpf D, et al. Comparing three CPR feedback devices and standard BLS in a single rescuer scenario: a randomised simulation study. Resuscitation 2014; 85(4): 560-6.

- Dold SK, Schmölzer GM, Kelm M, Davis PG, Schmalisch G, Roehr CC. Training neonatal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: can it be improved by playing a musical prompt? A pilot study. American journal of perinatology 2014; 31(03): 245-8.

- Cheng A, Brown LL, Duff JP, et al. Improving cardiopulmonary resuscitation with a CPR feedback device and refresher simulations (CPR CARES Study): a randomized clinical trial. JAMA pediatrics 2015; 169(2): 137-44.

- Yeung J, Davies R, Gao F, Perkins GD. A randomised control trial of prompt and feedback devices and their impact on quality of chest compressions—a simulation study. Resuscitation 2014; 85(4): 553-9.

- Fischer H, Gruber J, Neuhold S, et al. Effects and limitations of an AED with audiovisual feedback for cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a randomized manikin study. Resuscitation 2011; 82(7): 902-7.

- Noordergraaf GJ, Drinkwaard BW, van Berkom PF, et al. The quality of chest compressions by trained personnel: the effect of feedback, via the CPREzy, in a randomized controlled trial using a manikin model. Resuscitation 2006; 69(2): 241-52.

- Sutton RM, Niles D, Meaney PA, et al. “Booster” training: evaluation of instructor-led bedside cardiopulmonary resuscitation skill training and automated corrective feedback to improve cardiopulmonary resuscitation compliance of Pediatric Basic Life Support providers during simulated cardiac arrest. Pediatric critical care medicine: a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies 2011; 12(3): e116.

- Wik L, Thowsen J, Steen PA. An automated voice advisory manikin system for training in basic life support without an instructor. A novel approach to CPR training. Resuscitation 2001; 50(2): 167-72.

- Beckers SK, Skorning MH, Fries M, et al. CPREzy™ improves performance of external chest compressions in simulated cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2007; 72(1): 100-7.

- Perkins GD, Augré C, Rogers H, Allan M, Thickett DR. CPREzy™: an evaluation during simulated cardiac arrest on a hospital bed. Resuscitation 2005; 64(1): 103-8.

- Skorning M, Derwall M, Brokmann J, et al. External chest compressions using a mechanical feedback device. Der Anaesthesist 2011; 60(8): 717.

- Dine CJ, Gersh RE, Leary M, Riegel BJ, Bellini LM, Abella BS. Improving cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality and resuscitation training by combining audiovisual feedback and debriefing. Critical care medicine 2008; 36(10): 2817-22.

- Handley AJ, Handley SA. Improving CPR performance using an audible feedback system suitable for incorporation into an automated external defibrillator. Resuscitation 2003; 57(1): 57-62.

- Skorning M, Beckers SK, Brokmann JC, et al. New visual feedback device improves performance of chest compressions by professionals in simulated cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2010; 81(1): 53-8.

- Elding C, Baskett P, Hughes A. The study of the effectiveness of chest compressions using the CPR-plus. Resuscitation 1998; 36(3): 169-73.

- Sutton RM, Donoghue A, Myklebust H, et al. The voice advisory manikin (VAM): an innovative approach to pediatric lay provider basic life support skill education. Resuscitation 2007; 75(1): 161-8.

- Isbye DL, Høiby P, Rasmussen MB, et al. Voice advisory manikin versus instructor facilitated training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2008; 79(1): 73-81.

- Oh JH, Lee SJ, Kim SE, Lee KJ, Choe JW, Kim CW. Effects of audio tone guidance on performance of CPR in simulated cardiac arrest with an advanced airway. Resuscitation 2008; 79(2): 273-7.

- Rawlins L, Woollard M, Williams J, Hallam P. Effect of listening to Nellie the Elephant during CPR training on performance of chest compressions by lay people: randomised crossover trial. Bmj 2009; 339: b4707.

- Woollard M, Poposki J, McWhinnie B, Rawlins L, Munro G, O'meara P. Achy breaky makey wakey heart? A randomised crossover trial of musical prompts. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ 2012; 29(4): 290-4.

- Khanal P, Vankipuram A, Ashby A, et al. Collaborative virtual reality based advanced cardiac life support training simulator using virtual reality principles. Journal of biomedical informatics 2014; 51: 49-59.

- Park C, Kang I, Heo S, et al. A randomised, cross over study using a mannequin model to evaluate the effects on CPR quality of real-time audio-visual feedback provided by a smartphone application. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine 2014; 21(3): 153-60.

- Williamson L, Larsen P, Tzeng Y, Galletly D. Effect of automatic external defibrillator audio prompts on cardiopulmonary resuscitation performance. Emergency medicine journal 2005; 22(2): 140-3.

- Mpotos N, Yde L, Calle P, et al. Retraining basic life support skills using video, voice feedback or both: a randomised controlled trial. Resuscitation 2013; 84(1): 72-7.

- Roehr CC, Schmölzer GM, Thio M, et al. How ABBA may help improve neonatal resuscitation training: auditory prompts to enable coordination of manual inflations and chest compressions. Journal of paediatrics and child health 2014; 50(6): 444-8.

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. Journal Of The American Medical Association 2006; 296(9): 1094-102.

- Weidman EK, Bell G, Walsh D, Small S, Edelson DP. Assessing the impact of immersive simulation on clinical performance during actual in-hospital cardiac arrest with CPR-sensing technology: A randomized feasibility study. Resuscitation 2010; 81(11): 1556-61.

- Kluger AN, DeNisi A. The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol Bull 1996; 119(2): 254.

- Hatala R, Cook DA, Zendejas B, Hamstra SJ, Brydges R. Feedback for simulation-based procedural skills training: a meta-analysis and critical narrative synthesis. Advances in Health Sciences Education 2014; 19(2): 251-72.

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education. The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: American Education Research Association, 2014.

- Contri E, Cornara S, Somaschini A, et al. Complete chest recoil during layperson’s CPR: Is it a matter of weight? The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2017; 35(9): 1266-8.

- Bildik F, Gunendi Z, Aslaner AM, et al. The relationship between upper extremity functional performance and anthropometric features and the quality criteria of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Tuk J Phys Med Rehabil 2022; 68(3): 348-54.

- Bibl K, Gropel P, Berger A, Schmolzer GM, Olischar M, Wagner M. Randomised simulation trial found an association between rescuers’ height and weight and chest compression quality during paediatric resuscitation. Acta paediatrica 2020; 109(9): 1831-7.

- Schroeder DC, Semeraro F, Greif R, et al. KIDS SAVE LIVES: Basic Life Support Education for Schoolchildren: A Narrative Review and Scientific Statement From the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation 2023; 147(24): 1854-68.

- Lo BM, Devine AS, Evans DP, et al. Comparison of traditional versus high-fidelity simulation in the retention of ACLS knowledge. Resuscitation 2011; 82(11): 1440-3.

- Settles J, Jeffries PR, Smith TM, Meyers JS. Advanced cardiac life support instruction: do we know tomorrow what we know today? Journal of continuing education in nursing 2011; 42(6): 271-9.

- Cheng Y, Xue FS, Cui XL. Removal of a laryngeal foreign body under videolaryngoscopy. Resuscitation 2013; 84(1): e1-2.

- Cherry RA, Williams J, George J, Ali J. The effectiveness of a human patient simulator in the ATLS shock skills station. The Journal of surgical research 2007; 139(2): 229-35.

- Conlon LW, Rodgers DL, Shofer FS, Lipschik GY. Impact of levels of simulation fidelity on training of interns in ACLS. Hospital practice (1995) 2014; 42(4): 135-41.

- Coolen EH, Draaisma JM, Hogeveen M, Antonius TA, Lommen CM, Loeffen JL. Effectiveness of high fidelity video-assisted real-time simulation: a comparison of three training methods for acute pediatric emergencies. International journal of pediatrics 2012; 2012: 709569.

- Curran V, Fleet L, White S, et al. A randomized controlled study of manikin simulator fidelity on neonatal resuscitation program learning outcomes. Advances in health sciences education : theory and practice 2015; 20(1): 205-18.

- Donoghue AJ, Durbin DR, Nadel FM, Stryjewski GR, Kost SI, Nadkarni VM. Effect of high-fidelity simulation on Pediatric Advanced Life Support training in pediatric house staff: a randomized trial. Pediatr Emerg Care 2009; 25(3): 139-44.

- Finan E, Bismilla Z, Whyte HE, Leblanc V, McNamara PJ. High-fidelity simulator technology may not be superior to traditional low-fidelity equipment for neonatal resuscitation training. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association 2012; 32(4): 287-92.

- Hoadley TA. Learning advanced cardiac life support: a comparison study of the effects of low- and high-fidelity simulation. Nursing education perspectives 2009; 30(2): 91-5.

- Owen H, Mugford B, Follows V, Plummer JL. Comparison of three simulation-based training methods for management of medical emergencies. Resuscitation 2006; 71(2): 204-11.

- Thomas EJ, Williams AL, Reichman EF, Lasky RE, Crandell S, Taggart WR. Team training in the neonatal resuscitation program for interns: teamwork and quality of resuscitations. Pediatrics 2010; 125(3): 539-46.

- Campbell DM, Barozzino T, Farrugia M, Sgro M. High-fidelity simulation in neonatal resuscitation. Paediatrics & Child Health 2009; 14(1): 19-23.

- King JM, Reising DL. Teaching advanced cardiac life support protocols: the effectiveness of static versus high-fidelity simulation. Nurse educator 2011; 36(2): 62-5.

- Rodgers DL, Securro S, Jr., Pauley RD. The effect of high-fidelity simulation on educational outcomes in an advanced cardiovascular life support course. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare 2009; 4(4): 200-6.

- Soar J, Donnino MW, Maconochie I, et al. 2018 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations Summary. Resuscitation 2018; 133: 194-206.

- Cheng A, Lang TR, Starr SR, Pusic M, Cook DA. Technology-enhanced simulation and pediatric education: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2014; 133(5): e1313-23.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Admitted patient care 2014–15: Australian hospital statistics. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health services series no. 68. Cat. no. HSE 172. Retrieved 6 September 2018 from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/ahs-2014-15-admitted-patient-care/contents/table-of-contents, 2016.

- New Zealand Ministry of Health. Publicly funded hospital discharges – 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2016. 2018.

- Fennessy G, Hilton A, Radford S, Bellomo R, Jones D. The epidemiology of in‐hospital cardiac arrests in Australia and New Zealand. Int Med J 2016; 46(10): 1172-81.

- Kaczorowski J, Levitt C, Hammond M, et al. Retention of neonatal resuscitation skills and knowledge: a randomized controlled trial. Family medicine 1998; 30(10): 705-11.