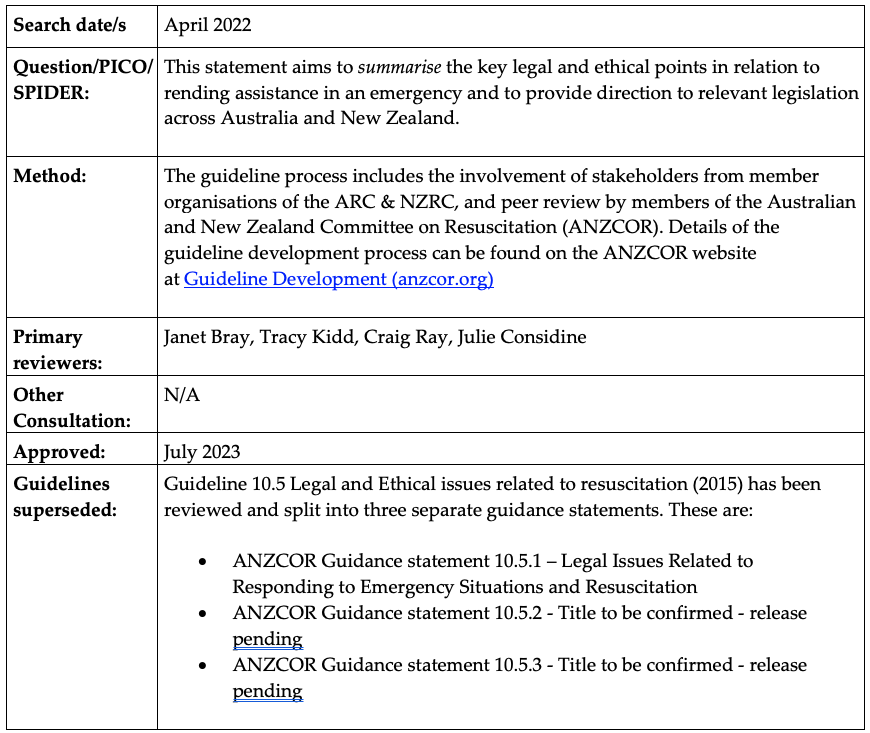

Search

Guidance Statement 10.5.1 – Legal Issues Related to Responding to Emergency Situations and Resuscitation

Statement

This statement does not constitute legal advice.

This statement aims to summarise the key legal and ethical points in relation to rending assistance in an emergency and to provide direction to relevant legislation across Australia and New Zealand. It should only be used as a guide to these legal and ethical issues. Individuals and/or organisations should obtain legal advice if required for their own jurisdiction.

Summary

ANZCOR strongly encourages members of the Australian and New Zealand public, including volunteers and off-duty health care professionals, to render assistance in emergency situations after considering risks to their own safety.

A Good Samaritan is generally defined as a person who, in good faith and without expectation of payment or reward, comes to the aid of another (or others) in an emergency situation.

Some members of the public remain concerned about rending assistance out of fear of causing harm and being exposed to the potential for legal liability. However, Australian and New Zealand law protects such Good Samaritans to ensure people come to the assistance of others in need. No person acting as a Good Samaritan in Australia has ever been successfully sued for rending assistance to a person in need and is generally protected by law if the rescuer acts in good faith and is not reckless.

Good Samaritans generally have no legal obligation to assist another (with the exception of those in the Northern Territory). However, any attempt at resuscitation is better than no attempt within the guidelines of one’s training, and we encourage anyone to help another in need of emergency assistance when it is safe to do so.

Health professionals are bound by codes of conduct and legislation in their jurisdiction and therefore need to be aware of the obligations. They must perform their tasks to a standard expected of a reasonably competent person with their training and experience.

Those teaching resuscitation and first aid should empower their learners with the ability to make informed decisions on the appropriate actions to take.

General Principles

- A Good Samaritan is defined in legislation as a person who is present at an emergency and assists in good faith, without expectation of payment or reward for providing assistance.

- Good Samaritans may include bystanders, family members, volunteers, and off-duty health professionals.

- Volunteers may differ from Good Samaritans, as they may have some medical training or be purposely engaged to assist others (e.g. a surf lifesaver). What classifies a Volunteer changes between jurisdictions, however, the common characteristics are that the work done is on a voluntary basis and for benevolent, sporting, educational, cultural, or non-financial purposes. Volunteers must act within the scope of activity and instructions of their organisation. When not on duty, trained Volunteers would be regarded as Good Samaritans if deciding to render assistance.

- A medical professional will be excluded as being a Good Samaritan if they attend with the expectation of reward or payment of services.

Duty to Rescue and Legal Protections

In Australia

- Bystanders or those in attendance at an injury or illness generally have no legal obligation to assist a fellow human being.

- Only the Northern Territory has legislation that imposes a duty to render assistance in an emergency. In that jurisdiction, any person who callously fails to provide assistance of any kind to a person urgently in need of it and whose life may be endangered may be guilty of a crime and if found liable may face imprisonment for up to 7 years (Criminal Code Act 1983, s155).

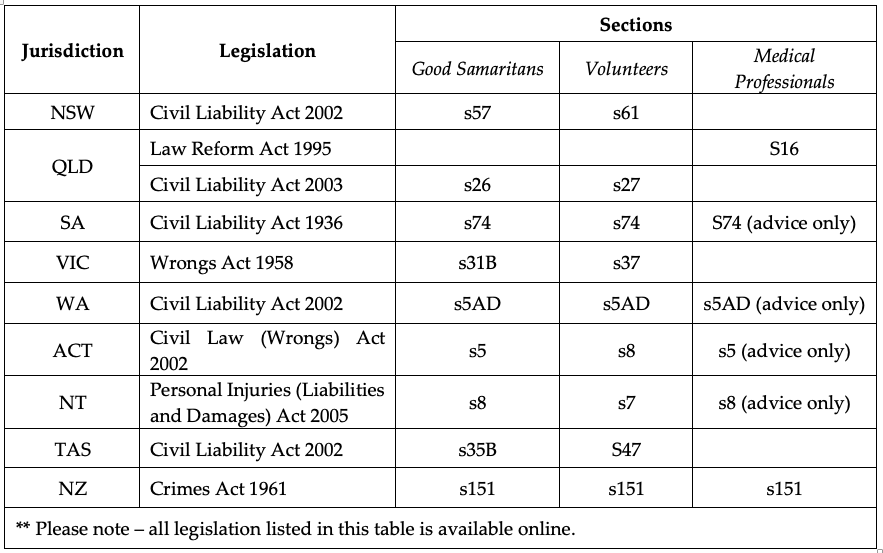

- All Australian jurisdictions have legal protections for Good Samaritans (Table 1).

- Good Samaritans have complete immunity from civil liability provided they are not under the voluntary influence of drugs or alcohol if they did not cause the emergency, and if they act in good faith.

- No Good Samaritan or Volunteer in Australia has ever been successfully sued for consequences of rendering assistance to a person in need. The Courts do not want to dissuade people from coming to the assistance of others.

In New Zealand

- New Zealand does not have explicit protection of Good Samaritans. There is a duty to render assistance to another.

- The wording “actual care” is not defined in the legislation and could apply to a person who helps another and provides ‘actual care’ to them.

Duty of care

- Having decided to assist, a rescuer owes a duty of care and is expected to display a standard of care appropriate to their training (or lack of training).

- Health professionals are subject to legal, ethical, and professional principles. Health care professionals need to be aware of the relevant legislation in their jurisdiction (Table 1 and Appendix 1).

Table 1. Good Samaritan legislation (current as of search date April 2022)

Australian Legislation

Current as of search date April 2022

Commonwealth

- Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009 (Cth)

- Good Medical Practice: A Code of Conduct for Doctors in Australia

Australian Capital Territory

- Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002 (ACT) s 5, 8

New South Wales

- Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) ss57, 61

- Health Practitioner Regulation (Adoption of National Law Act) (NSW) 2009 No 86

Victoria

- Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic) s 31B, 37

South Australia

- Civil Liability Act 1936 (SA) s 74

Queensland

- Law Reform Act 1995 (QLD) s 16

- Civil Liability Act 2003 (QLD) s 26, 27

Tasmania

- Civil Liability Act 2002 (Tas) s35B, s47

Western Australia

- Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA) s5AD

- Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (WA) Act 2010

Northern Territory

- Criminal Code Act 1983 (NT) s.155

- Personal Injuries (Liabilities and Damages) Act 2005 (NT) s8, 8

New Zealand Legislation

Current as of search date April 2022

- Crimes Act 1961 (NZ) s151

References

- Tibballs J. Legal liabilities for assistance and lack of assistance rendered by Good Samaritans, Volunteers and their organisations. Insurance Law Journal 2005;16:254-80.

- Higgins T (Chief Justice). The rescuer’s duty of care. Royal Life Saving Society Quinquennial Commonwealth Conference. Bath. 26/9/2006.

- Skene L. Law and Medical Practice, Rights, duties, Claims and Defences. 3rd edition, Australia, LexisNexus, 2008.

- Queensland Government. Implementation guidelines. End-of-life care: Decision-making for withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining measures from adult patients. Part 1.

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. A National Framework for Advance Care Directives, Sept 2011. <www.aph.gov.au>

- Kerridge I, Lowe M, McPhee J. Ethics and law for the health professions. 4th ed. Federation Press, Leichhardt NSW, 2013.

- Soar J, Mancini ME, Bhanji F et al. Education, Implementation, and Teams. 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations, Part 12. Resuscitation 2010;81:e288–e330.

- Kleinman ME, de Caen AR, Chameides L et al. Pediatric Basic and Advanced Life Support: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations, Part 10. Circulation. 2010;122(Suppl 2):S466-S515.

- Maconochie IK, de Caen AR, Aickin R, Atkins DL, Biarent D, Guerguerian AM, Kleinman ME, Kloeck DA, Meaney PA, Nadkarni VM, Ng KC, Nuthall G, Reis AG, Shimizu N, Tibballs J, Pintos RV. Part 6: Pediatric basic life support and pediatric advanced life support 2015 International Consensus on cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation 2015: 95: e147-e168.

- Slater + Gordon Lawyers (2019) Public Liability – What is duty of care? Online at: https://www.slatergordon.com.au/personal-injury/public-liability/what-is-duty-of-care

- Victorian State Government (2017) Voluntary Assisted Dying Overview. Online at: https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/hospitals-and-health-services/patient-care/end-of-life-care/voluntary-assisted-dying/vad-overview

About this Guidance Statement

Appendix 1. Related Health Professional Legislation in Australia and New Zealand

Health care professionals in Australia:

- New South Wales and Western Australia are the only two states to have adopted Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009 into State legislation. In New South Wales, Health professionals who have been requested to provide assistance outside their usual place of work when ready for duty, have a legal obligation to do so in accordance with Health Practitioner Regulation (Adoption of National Law Act) (NSW) 2009 No 86 s139C(c). A medical professional must attend, within a reasonable time after being so requested, a person who the medical practitioner knows or has reasonable cause to believe may require urgent care. The medical professional must attend to render aid in a professional capacity unless they take all reasonable steps to ensure that another competent medical professional attends instead within a reasonable time. A failure to attend a person requiring urgent aid or organising a replacement medical practitioner can be found guilty of unprofessional conduct and subject to disciplinary review.

- Western Australia also considers that a medical professional who fails to uphold the standard and conduct of the profession is guilty of unsatisfactory conduct, which can amount to disciplinary review. The Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (WA) Act 2010 does not detail unsatisfactory conduct like New South Wales, however, it does recognise the professional and ethical standards present in Policy and Codes of Conduct and a failure to abide by them amounts to a contravention of the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (WA) Act 2010.

- Northern Territory: When attending to a person requiring aid, health professionals have a higher standard of expectation to assist and a standard of care because of the Criminal Code Act 1983

- Other Australian jurisdictions: Although the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009 also applies to other Australian jurisdictions (as a national law), it does not contain a section specifying that failure to render urgent assistance is unsatisfactory professional conduct. However, a doctor in any jurisdiction who fails to render emergency assistance to a victim may be subject to legal or disciplinary action since section 2.5 of the code of medical practice (Good Medical Practice: A Code of Conduct for Doctors in Australia) states: “Good medical practice involves offering emergency assistance in an emergency that takes account of your safety, your skills, the availability of other options and the impact on any other patients under your care; and continuing to provide that assistance until your services are no longer required”.

Health care professionals in New Zealand:

- In New Zealand, the Crimes Act 1961 (s151) requires a person in charge of another by reason of detention, age, sickness insanity, or any other cause, to provide the “necessaries of life” to preserve life and prevent permanent injury and if neglecting to do so is criminally liable unless a lawful excuse exists. Such excuses would be good medical practice in the victim’s best interests.

- Right 4(s2) of the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights, lawful as a regulation under the Health and Disability Commissioner Act (1994), provides that every consumer has a right to have services provided that comply with legal, professional, ethical and relevant other standards. The Code extends to every registered health professional person or organisation providing a health service to the public whether remunerated or not.

- Furthermore, the New Zealand Medical Association’s Code of Ethics specifies that a doctor has a duty to attend a medical emergency if requested, and that ethical duty is a legal requirement for doctors under the Act. In this context, an emergency is defined as a sudden unforeseen injury, illness, or complication demanding immediate early professional care to save or prevent gross disability, pain, or distress.

- Ethical and therefore lawful excuses to not attend an emergency are:

- attendance at another emergency,

- existence of a more appropriate or geographically available service,

- the doctor is off-duty and impaired by alcohol or medication,

- attendance places the doctor at personal risk,

- the doctor is unable to provide a level of care necessary for the emergency, for example if impeded by fatigue,

- inability to attend the emergency for any reason does not expiate the medical duty of care to assist in the provision of alternative health care.

Referencing this guideline

When citing the ANZCOR Guidelines we recommend:

ANZCOR, 2025, Guidance Statement 10.5.1 – Legal Issues Related to Responding to Emergency Situations and Resuscitation, accessed 3 July 2025, https://www.anzcor.org/home/education-and-implementation/anzcor-guidance-statement-10-5-1-legal-issues-related-to-responding-to-emergency-situations-and-resuscitation/